Introduction: A Region Rich in Potential, Trapped by Systems Failure

Lango, home to nearly three million people across districts such as Lira, Apac, Oyam, Kole, Dokolo, Alebtong, Amolatar, and Otuke, is a region of deep communal solidarity, cultural pride, and agricultural promise. Its land is fertile, its people industrious, and its informal social institutions, clans, churches, burial societies, and savings groups, continue to absorb shocks where the state falls short.

Yet in 2025, Lango remained caught in a familiar paradox: high resilience, low returns.

This is not because the region lacks ideas. Development plans exist. Manifestos are written. Leaders articulate the right priorities. Communities know what they need: passable roads, electricity, functional schools and health centres, predictable markets, secure land, and jobs that reward effort. What Lango carries instead is unfinished post-conflict history, fragile livelihoods, and a fragmented leadership ecosystem that often competes for visibility rather than coordinating power. This combination has become emotionally exhausting for ordinary families turning farming seasons into gambles, school terms into negotiations, and elections into cycles of hope followed by disappointment.

This Op-Ed is not a complaint.

It is a diagnosis.

And diagnoses matter because without clarity, treatment fails.

1) A Dignity Crisis: Peace Without Prosperity

Lango is often described as peaceful. That is true. But peace without progress is not dignity.

Families survived displacement camps, cattle rustling, and prolonged insecurity that stripped assets and trust. Recovery was largely self-driven: homes rebuilt slowly, livestock never fully restored, children sent back to overcrowded schools where absenteeism became normal.

By 2025, many people felt excluded from Uganda’s national growth story. While the country spoke of highways, oil, and urban expansion, Lango experienced a harsher reality:

- Youth unemployment and underemployment persisted, especially in Lira City and Apac Town, where many young people remained stuck in boda-boda riding and petty trade.

- Agriculture, the region’s backbone, remained low-value and poorly commercialized, with post-harvest losses often exceeding 30%.

- Public services were unreliable drug stock-outs, broken water points, impassable roads.

- Corruption and absenteeism were experienced directly, not abstractly.

The frustration is not ideological; it is experiential. People measure effort against outcome and find the gap humiliating. They work hard, vote faithfully, and wait patiently, but returns remain thin. Anger rises not because government exists, but because it feels distant and unaccountable. When dignity erodes, trust follows. When trust collapses, development stalls.

2) Cultural Leadership Disputes and the Loss of Collective Voice:

Historically, Lango’s cultural institutions played a stabilizing, non-partisan role, mediating disputes, enforcing norms, and uniting clans. In 2025, that role fractured. Cultural leadership disputes became public and politicized; creating confusion over who legitimately speaks for Lango. This fragmentation had concrete consequences:

- During Presidential engagements, multiple voices presented overlapping and sometimes competing messages, weakening follow-through.

- In land and cattle disputes, uncertainty over cultural authority complicated mediation and pushed conflicts into courts and politics.

- In regional advocacy, Lango struggled to negotiate as a unified bloc, unlike regions that mobilized around consolidated cultural, political fronts.

This matters because cultural cohesion is not ceremonial, it is a governance asset. Fragmented culture produces fragmented advocacy, which weakens bargaining power and reduces the region’s ability to secure resources and accountability. In 2025, Lango did not lose influence because it lacked issues. It lost leverage because it lacked unity of voice.

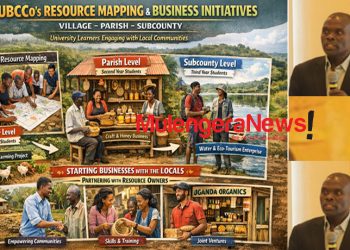

3) Youth Unemployment: A Social Stability Issue, Not Just an Economic One

Lango is young, but opportunity is narrow and outdated. In 2025, thousands of educated young people returned to villages and towns with no land, no capital, and no pathway into productive adulthood. What followed was not laziness, but stagnation.

This produced three dangerous consequences:

- Security risk – Idle youth became easier to recruit into petty crime, alcohol abuse, and political muscle-for-hire.

- Political distortion – Small handouts replaced policy debate; desperation became political currency.

- Social breakdown – Marriage, family formation, and enterprise were delayed, weakening community continuity.

This is not unemployment alone. It is a legitimacy crisis. No society remains stable when a large generation feels permanently postponed.

4) Agriculture Feeds the Region but Not Its People

Over 70% of households in Lango depend on agriculture, yet in 2025 it remained subsistence-oriented rather than income-driven. Farmers produced maize, cassava, sunflower, rice, soybeans, and livestock but sold raw produce immediately after harvest due to lack of storage, processing, finance, and markets. The result was stark:

Lango exported raw value and imported finished cost.

This was not farmer failure. It was structural exclusion from value chains. Poverty persisted not because of inactivity, but because economic architecture was missing. Until agriculture is treated as a business through aggregation, processing, standards, finance, and contracts; every speech on jobs and growth will remain hollow.

5) Infrastructure in 2025 Determined Who Participated and Who Was Locked Out:

Infrastructure failure in 2025 was visible, debated, and raised directly to the President. Two roads symbolized the crisis:

- Amolatar’s road network, among the worst nationally, isolated lakeshore communities, forcing fishers and farmers into distress sales.

- The Lira–Otuke road, which became impassable for months, effectively cutting Otuke off from markets and services.

Electricity access outside Lira City remained low. Youth enterprises collapsed under generator costs. Health workers conducted night deliveries by torchlight, contradicting national health ambitions.

The conclusion was unavoidable:

Infrastructure gaps did not slow growth; they sorted citizens into participants and non-participants based on geography.

6) Land Conflict and Cattle Compensation: Unfinished Justice

Land conflict intensified in 2025 as population growth, urban expansion, and commercial agriculture pressure collided with unresolved post-conflict claims. Land disputes were raised repeatedly to the President, in Parliament, and in districts. Land in Lango is not just property; it is identity, inheritance, and justice. Without tenure certainty, investment stalls, youth remain landless, and peace dividends erode.

Cattle compensation, meanwhile, returned to the centre of national debate with a new Presidential proposal: stop cash compensation and give each affected household five head of cattle. While emotionally resonant, the proposal generated anxiety due to unanswered questions about verification, equity, quality, and governance. Communities did not reject it, they feared unfair implementation.

The lesson from 2025 is clear:

Cattle compensation is not an economic intervention. It is a justice process.

Handled poorly, it will divide. Handled transparently, it can heal.

7) 2026 Elections: Risk or Reset?

By the end of 2025, Lango faced a volatile convergence: service delivery failures, youth frustration, unresolved grievances, and elections. Service delivery failures hardened into political grievances. Youth frustration became mobilisable energy. Historical injustices entered campaign rhetoric. Trust thinned.

If unmanaged, 2026 will amplify division.

If guided with discipline, it can become a reset.

What Lango Must Do in 2026!

Lango’s leaders and policymakers must move from rhetoric to discipline:

- Adopt a Lango Minimum Agenda with non-negotiable priorities, roads, electricity, agro-processing, youth jobs, land governance, cattle justice.

- Shift from projects to systems, aggregation, skills-to-jobs pipelines, energy, enterprise corridors.

- Treat cattle compensation as a governance test, with verification, audits, and transparency.

- Restore trust through proof, not promises, publish data, empower citizen oversight.

- Depoliticize culture and restore unity, so Lango can bargain as one.

Closing Charge:

Lango’s people are not asking for miracles. They are asking for seriousness, coherence, and respect. 2026 can be a risk or a reset. The difference will not be made at rallies, but in quiet, disciplined decisions taken now. Lango has endured worse than an election season. What it cannot endure is another cycle of promises without proof.

The choice is still open but not for long!!