By Fredrick ES Mutengeesa

Introduction: A Nation Forced to Ask Painful Questions

Uganda today stands at a moral crossroads.

It is a nation increasingly compelled to confront uncomfortable, even devastating truths about itself. Corruption has grown so entrenched that many citizens now openly question the meaning of elections, the credibility of leadership, the purpose of public service, and, in moments of despair, the very idea of national identity.

One cannot escape the haunting questions whispered in homes, workplaces, and public spaces:

Has corruption become the accepted order of the day?

Has dishonesty become the currency of success?

This is no longer an abstract or academic debate. Corruption in Uganda has evolved beyond isolated scandals and individual wrongdoing. It has become systemic, cultural, and intergenerational.

It penetrates education, governance, religion, banking, taxation, elections, and even family life. Despite strong public rhetoric against corruption and the existence of multiple anti-corruption institutions, the disease persists, adapts, and deepens.

The central issue, therefore, is not whether Uganda has laws, policies, or agencies to fight corruption.

The more urgent question is whether the nation has been courageous enough to confront the true roots of corruption.

Corruption Begins Long Before Public Office: Homes and Schools

Contrary to popular belief, corruption does not begin in ministries, Parliament, or public offices. It begins much earlier—quietly and almost invisibly— in homes, nurseries, classrooms, and playgrounds.

School Placement and the Normalisation of Bribery

Across both private and government-aided schools, it has become disturbingly common for parents with financial means or social connections to secure places for their children in so-called “good schools” through bribery, favours, or influence.

In many cases, the children themselves are fully aware that admission was not earned on merit.

From a very young age, they absorb a dangerous lesson:

Money and influence matter more than rules, fairness, or hard work.

This becomes their first initiation into corruption. Procedures are no longer seen as principles to be respected, but as obstacles to be bypassed.

Integrity is not admired; it is quietly dismissed as impractical.

Examination Malpractice and Institutional Complicity

As learners advance through primary and secondary education, the moral decay often deepens. Examination malpractice—leaked papers, coached answers, impersonation, and collusion—has become a recurring national concern. Some teachers and school administrators, under pressure to maintain reputations and attract enrolment, sacrifice ethical standards for results.

Parents celebrate excellent grades. Schools advertise academic excellence.

Yet beneath the surface, children internalise a devastating message: success achieved dishonestly is still success.

By the time many students reach universities and tertiary institutions, bribery, favouritism, and manipulation feel normal. Integrity appears naïve.

Honesty feels like a liability.

From Education to Employment: Corruption as a Survival Strategy

When these young people enter the world of work, they carry with them the values they were taught—explicitly or implicitly.

Jobs, Promotions, and the Protection of Positions

In many government institutions and private organisations, recruitment, promotion, and job security are often shaped not by competence or performance, but by connections and payments.

Qualified individuals are sidelined, while less capable but better-connected individuals rise.

Even those who despise corruption frequently find themselves trapped in painful moral dilemmas:

Speak out and lose one’s job

Remain silent to protect one’s livelihood

Compromise to shield relatives or children from consequences

Corruption, therefore, is not merely practised—it is protected, justified, normalised, and inherited.

Banking, Loans, and Financial Corruption

The financial sector is not immune.

In some instances, individuals seeking legitimate loans—loans they fully intend to repay—are compelled to bribe officials simply to have applications processed or approved.

Such practices distort financial systems, exclude honest citizens, and reward manipulation.

They reinforce the corrosive belief that nothing moves without corruption.

Taxation: A Rotting Pillar of National Development

Taxation, the backbone of national development, has become another arena of moral collapse.

Both local government revenue systems and central authorities, including the Uganda Revenue Authority (URA), have faced persistent allegations of corruption:

Under-assessment of taxes

Negotiated tax liabilities

Selective enforcement

Collusion between officials and taxpayers

The result is deeply destructive.

Honest taxpayers feel punished for their integrity, while dishonest actors prosper. Public trust erodes.

The nation is deprived of resources desperately needed for healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social protection.

Government Institutions, Committees, and the Abuse of Public Resources

Across ministries, departments, agencies, and committees, corruption manifests in familiar but devastating forms:

Inflated procurement contracts

Ghost projects

Misuse of public funds

Selective and politicised accountability

Even institutions mandated to fight corruption have, at times, been accused of internal compromise. This creates a tragic paradox: the guardians themselves require guarding.

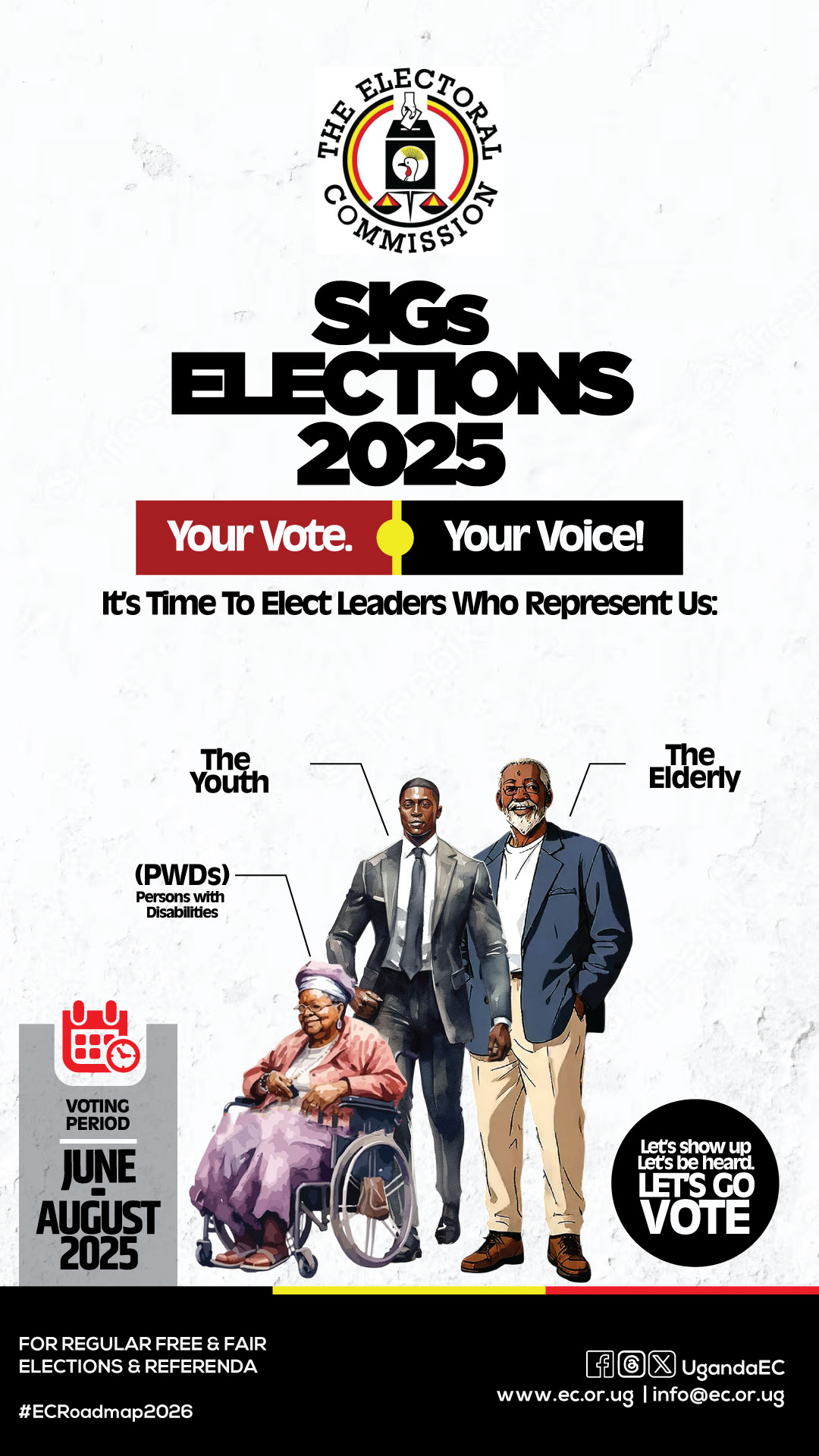

Elections: Leadership Reduced to a Commercial Enterprise

Elections—meant to be expressions of the people’s will—have increasingly become financial contests. Leadership is no longer understood primarily as service, but as investment.

Candidates sell property, incur crippling debts, and spend vast sums to:

Secure party endorsements

Influence internal primaries

Buy votes Once elected, public office becomes a mechanism for cost recovery.

Corruption is not accidental; it is structural and predictable.

This reality explains the persistent cycles of electoral violence, manipulation, and public disillusionment.

Religious Institutions and the Tragedy of Moral Silence

Perhaps the most painful contradiction is the penetration of corruption into religious spaces. Individuals who accumulate wealth through questionable means are often celebrated because of their financial contributions.

When moral institutions fail to challenge corruption prophetically, society loses its conscience.

Silence becomes complicity.

The Silent Heroes: Those Who Refuse to Be Bought

Yet it must be stated clearly and without hesitation: not all Ugandans are corrupt.

Across the country are courageous teachers, civil servants, clergy, businesspeople, and young people who resist corruption daily.

Their integrity comes at a heavy price:

Career stagnation

Isolation

Threats and intimidation

Emotional and psychological exhaustion

These individuals are rarely celebrated, yet they are the true custodians of Uganda’s future.

The Cost of Corruption: A Nation Being Slowly Wounded

Corruption is not merely the theft of money. It is:

The killing of opportunity

The erosion of trust

The destruction of institutions

A threat to national stability

Uganda is not collapsing dramatically—it is bleeding quietly and persistently.

A Strategic Roadmap for National Moral and Institutional Renewal

Confronting corruption requires both bottom-up and top-down transformation:

1. Family-Level Moral Reorientation

Integrity must be taught, lived, and modelled at home.

2. Education Sector Reform

Transparent admissions, zero tolerance for examination malpractice, and institutional—not selective—accountability.

3. Protection of Whistle-blowers

Those who speak truth must be protected, not punished.

4. Electoral and Campaign Finance Reform

Politics must be de-commercialised and re-moralised.

5. Tax and Financial System Integrity

Automated, transparent systems with minimal human discretion.

6. Restoration of Religious Moral Authority

Faith institutions must reclaim their prophetic voice.

- Youth Economic Empowerment

Unemployment fuels corruption; opportunity weakens it.

Conclusion: Uganda Still Has a Choice

Corruption may never be eradicated completely.

But it can be controlled, reduced, and resisted.

Uganda’s future depends on the choices made today—between convenience and conscience, silence and truth, profit and principle.

The fight against corruption is not only legal or political. It is moral, cultural, and generational

And it must begin now — in our homes, in our schools, in our institutions, and in our hearts.

(For comments on this story, get back to us on 0705579994 [WhatsApp line], 0779411734 & 041 4674611 or email us at mulengeranews@gmail.com).