By Aggrey Baba

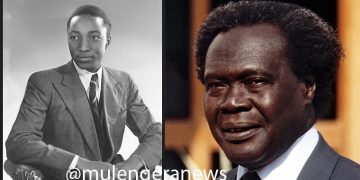

[Politics makes strange bedfellows], so goes a Luganda saying. And the story of Kabaka Edward Mutesa II and Milton Obote is one of unlikely political allies who later turned into bitter rivals, shaping Uganda’s destiny in the process.

On April 24, 1956, Sir Andrew Cohen, the Governor of the Uganda Protectorate, announced that direct elections to the Legislative Council (LegCo) would be held as a step toward Uganda’s self-rule. The announcement was received with excitement by the government of Kabaka Mutesa II in Mengo.

In response, on November 22, 1956, the Buganda Lukiiko, under the leadership of Raphael Kasule, formed a special committee to draft voter qualifications and candidate requirements. The committee, led by Amos Sempa (Mutesa’s Minister of Education), included notable members like Daniel Bakabulindi, Matiya Wamala, Ignatius Musaazi, and Joshua Luyimbazi.

The committee proposed strict qualifications, where a candidate had to be at least 26 years old, fluent in English, own property worth at least £200, and pay a registration fee of £50. For voters, one had to be at least 21 years old, own land, and have lived in Buganda for at least three years.

However, these qualifications were met with opposition from figures like Joseph William Kiwanuka (Jolly Joe), who argued they would disqualify many Baganda. As a result, some of the requirements were suspended.

Even as preparations for self-rule elections continued, trouble began brewing between Mengo and the colonial administration. Governor Cohen, instead of declaring election dates, shocked Mutesa’s government by announcing a plan to compulsorily acquire Buganda’s Mailo land for a railway extension to western Uganda.

The Buganda Lukiiko fiercely opposed this move, arguing it was a violation of land rights. Some members went as far as claiming that if the railway passed near Mengo Palace, it would disturb the Kabaka’s sleep at night.

As the standoff intensified, Buganda sent Sempa and Luyimbazi to London to seek legal counsel from British lawyers Roland Brown and Brian McKenna. The governor, however, remained firm, offering to suspend land acquisition only if a legal process was agreed upon.

Frustrated by the governor’s stance, the Lukiiko convened in February 1957 and formed a committee to list grievances that could justify Buganda’s secession from Uganda. Three main reasons were cited: the forced acquisition of land, the 1953 deportation of Kabaka Mutesa, and the British government’s plan to centralize East Africa’s military administration.

The Lukiiko then formed a team to prepare for Buganda’s breakaway, including Kintu, Godfrey Binaisa, Fred Mpanga, A.D. Lubowa, Dr. Emmanuel Lumu, and Amos Sempa.

As Buganda escalated its breakaway campaign, a brave young politician, Milton Obote, stepped in. On February 2, 1960, Obote held a press conference in Kampala, warning Mengo that African nationalism would not allow Buganda to exist as an independent state.

“Africa is rising. It wants to compete with Europe, America, and Asia. It will not tolerate a small kingdom making separate agreements with foreign powers,” Obote declared.

Obote strongly criticized Buganda’s call for an election boycott and even took issue with Governor Sir Frederick Crawford for inviting Mengo representatives to talks. Nevertheless, the governor postponed voter registration in Kampala to allow more discussions.

However, Obote was determined that elections proceed with or without Buganda’s participation. When the talks collapsed, 96% of registered voters in Buganda boycotted the elections. Yet, some Baganda, including Minister of Education Abu Mayanja, defied the boycott and voted for Obote’s Uganda People’s Congress (UPC).

The Democratic Party (DP), led by Benedicto Kiwanuka, won the majority and formed the government, with Kiwanuka as Uganda’s first Prime Minister.

Despite his opposition to Mengo’s politics, Obote saw an opportunity in Buganda’s deep resentment toward Kiwanuka’s Catholic-led DP government. Sensing British reluctance to grant independence under Kiwanuka, Obote devised a plan.

He approached Abu Mayanja and convinced him that if Mengo allied with UPC, they could push for fresh elections before independence. Excited by the idea, Mayanja sold it to Mengo’s Finance Minister, Amos Sempa, a staunch critic of Kiwanuka.

Mutesa, after discussions with Obote, was persuaded. In September 1961, the two met privately at Carlton Towers in London. Following these talks, Mutesa instructed Buganda Lukiiko to end its boycott and send representatives to the crucial Lancaster Conference, where Uganda’s independence constitution was being drafted.

This alliance bore fruit. Fresh elections were held before independence, and the UPC-Kabaka Yekka (KY) coalition won, making Obote Uganda’s first executive Prime Minister in 1962, while Mutesa was installed as the ceremonial President in 1963.

Like a house built on sand, the alliance was unstable from the start. By October 1963, just months after Mutesa was sworn in as President, cracks had already grown. On July 12, 1963, reconciliation talks were held in Entebbe between Obote and Mengo leaders, but all in vain.

Obote, sensing a threat from Mutesa and the KY, decided to act. On May 24, 1966, he ordered Colonel Idi Amin to storm Mengo Palace. Mutesa fled into exile in London, where he died in 1969.

In a strange twist of fate, a conversation in Mutesa’s former health minister Mawazi’s home foreshadowed the future. As the story goes, the minister’s child once asked, “Daddy, between Kabaka Mutesa and Obote, who is older?” The father replied, “Mutesa is one year older than Obote.” The child then asked, “Does that mean Mutesa will die first?” Disturbed by the question, the father angrily scolded the child. Yet, fate had already written its script. Mutesa died in exile on November 21, 1969, while Obote lived on for another 36 years, passing away on October 10, 2005. History, like the setting sun, had completed its cycle.

Mutesa and Obote’s story is one of political twists and turns. From bitter enemies to strategic allies and back to enemies, their political marriage shaped Uganda’s path to independence but also laid the foundation for later conflicts. (For comments on this story, get back to us on 0705579994 [WhatsApp line], 0779411734 & 041 4674611 or email us at mulengeranews@gmail.com).