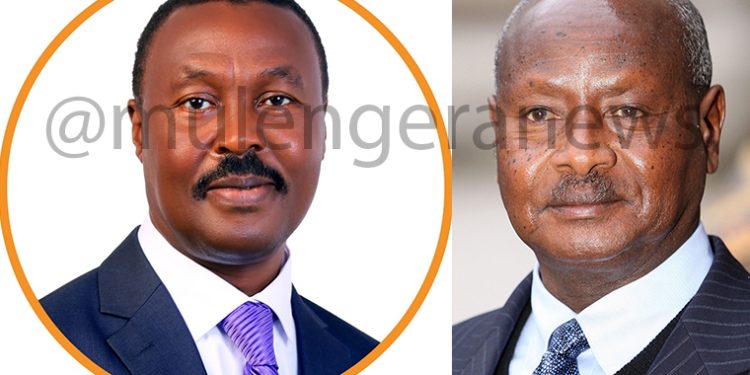

Former army commander Maj. Gen. (Rtd) Mugisha Muntu has for the first time in years revisited the painful turning points that drove him away from President Yoweri Museveni, saying the 1996 elections in Ntungamo District were the beginning of a leadership crisis that destroyed the Movement’s integrity.

Speaking during his campaign stop in Kalangala District, yesterday, the Alliance for National Transformation (ANT) presidential flag bearer narrated how the then-newly introduced Movement system began to lose direction when leaders at the top started meddling in lower-level elections.

yesterday,

He explained that as a soldier who had fought alongside Museveni during the bush war, he expected a new era of fairness and democracy after 1986. But by 1996, he could already see signs of manipulation and intolerance that were gradually replacing the ideals they once fought for.

According to Muntu, the conflict erupted during the Ntungamo LC5 elections when the NRM leadership attempted to impose a preferred candidate against the will of the people. As army commander at the time, he advised Museveni that such actions would corrupt the new system from within and plant the seeds of division.

When his warning was ignored, Muntu said, the events confirmed to him that the Museveni had started drifting from the principles that guided the liberation struggle, of unity, honesty, and equal opportunity for all.

He recalled that security officials, including then Security Minister Muruli Mukasa and General Kale Kayihura, were among those deployed to Ntungamo to mobilize for the preferred candidate. That, Mugisha noted, sent a dangerous signal that the military was being used to influence political outcomes.

“It was no longer about serving the people,” he said quietly, adding that the system was becoming about serving the powerful.

The former army commander added that the final break came during the controversial push to remove presidential term limits in the early 2000s. At the time, Muntu was among several senior Movement leaders invited to a six-day retreat at the National Leadership Institute in Kyankwanzi to deliberate on the matter. He said the majority of participants opposed the amendment, arguing that it would open the door to life presidency.

He revealed that the group had agreed to first consult the public, but Museveni later convened a closed meeting at Kyankwanzi and reversed the earlier consensus. The decision that emerged from that private meeting, Muntu said, betrayed the spirit of the liberation war.

The constitutional amendment was later passed at a massive Movement delegates’ conference, effectively removing term limits and allowing Museveni to contest indefinitely. For Muntu, that was the point of no return.

“That day, I knew the system we had built had completely lost direction,” he said.

Muntu also revisited the events of 2001, when Lt. Col (Rtd) Dr. Kizza Besigye challenged Museveni in the presidential race. He said that year, a radio advert aired claiming that he and other generals were openly backing Museveni’s re-election. As a serving soldier then, Muntu said he found the claim false and damaging, since it portrayed him as partisan. He immediately demanded a correction, insisting that every Ugandan (including soldiers) had a right to make their own political choices.

He emphasized that he had already begun distancing himself from partisan politics within the army, which he said was increasingly being used to secure political loyalty instead of national service.

He recalled that even before those events, in 1998, Museveni had offered him a ministerial position after relieving him of his duties as army commander.

He declined the offer, explaining that his disagreements were rooted in principle, not personal interest. He said he could not join a cabinet that rewarded corruption while punishing minor offenders.

“There were people stealing on a small scale who were being jailed, while those stealing in billions were being promoted,” Muntu noted. That decision, he explained, effectively sealed his exit from Museveni’s government.

Some residents of Kalangala, where Muntu shared his reflections, urged him to reconcile with Museveni, arguing that his departure had created a vacuum that allowed corruption to thrive.

Fred Mwanje, a veteran local leader, said if Muntu had stayed close to the President, maybe the country wouldn’t have reached this level of moral decay. But Muntu insisted that remaining silent within a decaying system would have been a greater betrayal.

“You cannot reform a system by becoming part of its rot,” he said.

Born in 1958, Muntu joined the bush war at 23, fresh from Makerere University, despite his father’s strong ties to the Obote regime. He fought alongside Museveni and other NRA soldiers, later heading Military Intelligence and serving as Army Commander from 1989 to 1998. After his military service, Muntu represented Uganda in the East African Legislative Assembly (EALA), later joined the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) as a founding member, and eventually formed the Alliance for National Transformation (ANT) after parting ways with Besigye in 2018.

As Uganda heads toward the 2026 elections, Muntu says he bears no personal grudge against Museveni but insists Uganda’s future lies in rebuilding trust, accountability, and respect for constitutional order. He maintains that the struggle today is no longer about who holds power, but about restoring the values that once gave Uganda a sense of purpose.